Christmas came early this year for the Salvation Army’s food pantry in Bismarck, North Dakota, thanks to the green thumbs at Basin Electric Power Cooperative.

Basin’s Backyard Garden has shipped more than 267 pounds of co-op-grown vegetables to the food pantry with an end-of-summer haul of 105 pounds of celery and potatoes.

The employee volunteer garden, now in its third year, is one of the pantry’s largest donors—and the need is evident.

“As soon as they bring it in, we weigh it and then it’s gone. It’s beautiful, and it’s free,” said LeAnn Knoll, the food pantry manager.

”The need is huge. So many people aren’t able to afford fresh vegetables or they don’t have time or space to garden,” said Knoll.

Spread out over a 1,700-square-mile area, people in need drive as much as 45 minutes for fresh produce. “In even more remote areas, there aren’t a lot of pantries available and they will deliver once a week or once a month,” said Knoll. “Basin is one of our bigger donors and we do thank them.”

The Bismarck G&T’s Tracie Bettenhausen, an avid gardener, began the garden and oversees volunteers who tend and harvest the vegetables. She checks the Hunger Free ND Garden Project, a database of charities accepting surplus produce

“Early in the summer, we have lots of radishes, and I know the older population loves fresh garden radishes like they used to grow on their own, so I make sure those harvests go to the Burleigh County Senior Center,” said Bettenhausen. “When we have large harvests of corn and potatoes later in summer, I usually direct the veggies to the Bismarck Emergency Food Pantry.”

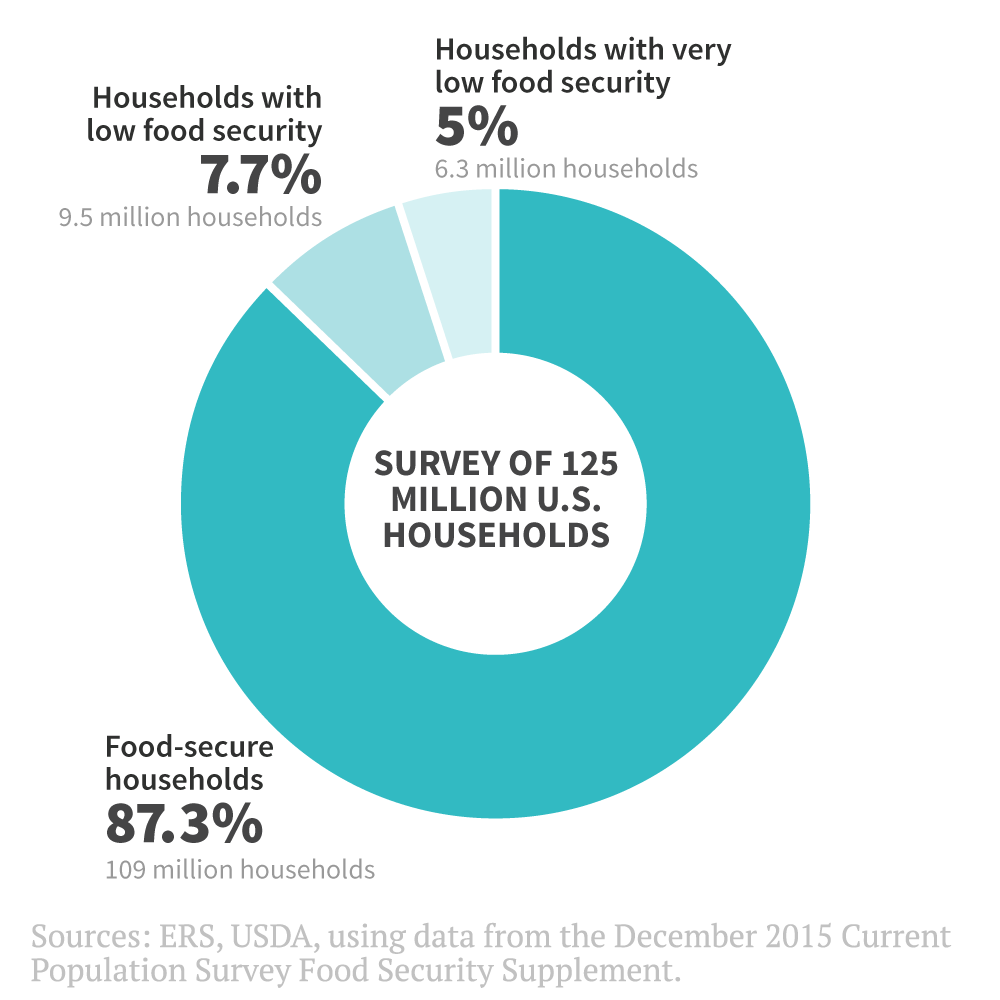

The employee garden’s one-ton yield is one of several efforts by electric co-ops to help members get enough food to eat. Food insecurity rates decreased last year to 12.7 percent from 14 percent in 2014, yet remain higher than before the Great Recession, according to recent data released by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Food Security Status of U.S. Households in 2015

“There are many reasons for food insecurity in rural communities,” said David Weaver, CEO of South Plains Food Bank in Lubbock, Texas. “Wages tend to be lower and the cost of food higher. There are not as many job opportunities. People are at greater risk of being unemployed or underemployed. Childcare and public transportation are also more of a drain on rural citizens.”

Recently, the food bank received a $10,000 grant from South Plains Electric Cooperative in Lubbock and CoBank to help it reach members that for several reasons have gone unserved. The grant will help the food bank defray costs of delivering food to remote communities.

“It’s a quality of life issue and that’s important to our cooperative goals: improving the quality of life for the members we serve,” said Lynn Simmons, the co-op’s director of communications.

Weaver said the food bank serves about 57,000 people in 28 counties. But, he added, statistics from the USDA and the Census Bureau show “there are 93,000 people we could be serving if we had the food and financial resources it takes to serve everyone.”

Together, the food bank and the co-op determined that 10 counties were falling between the cracks and that 23 agencies could serve as distribution points.

“The grant helps us close the gap,” said Weaver.

Victoria A. Rocha is an NRECA staff writer.