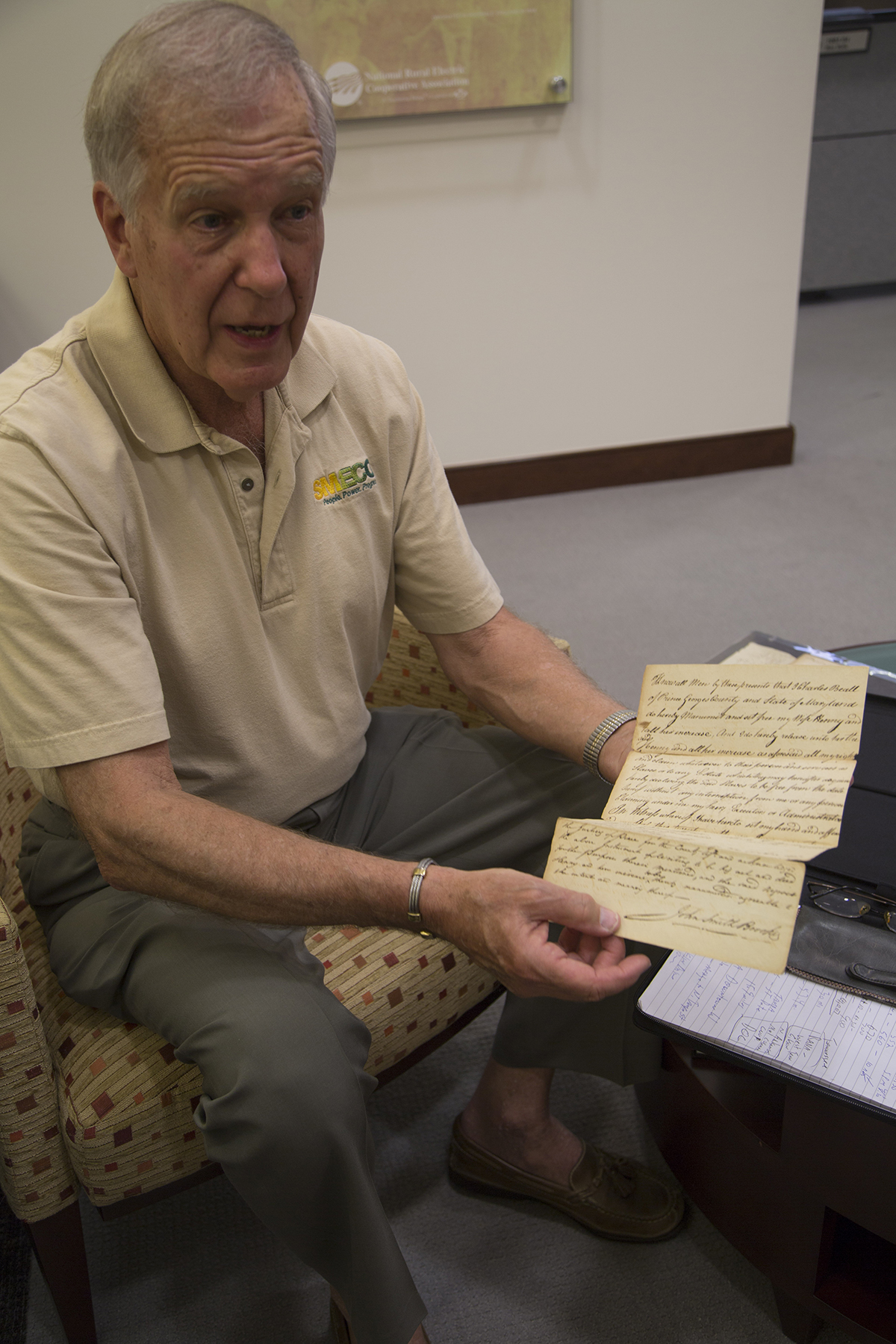

NRECA Maryland Director Danny Dyer has been attracting national attention these days, and not for rural electrification issues.

Media outlets have been carrying the story of Dyer’s remarkable find in a safe in his Accokeek, Maryland, home: a treasure trove of documents recording the freeing of slaves in Prince George’s County before the Civil War.

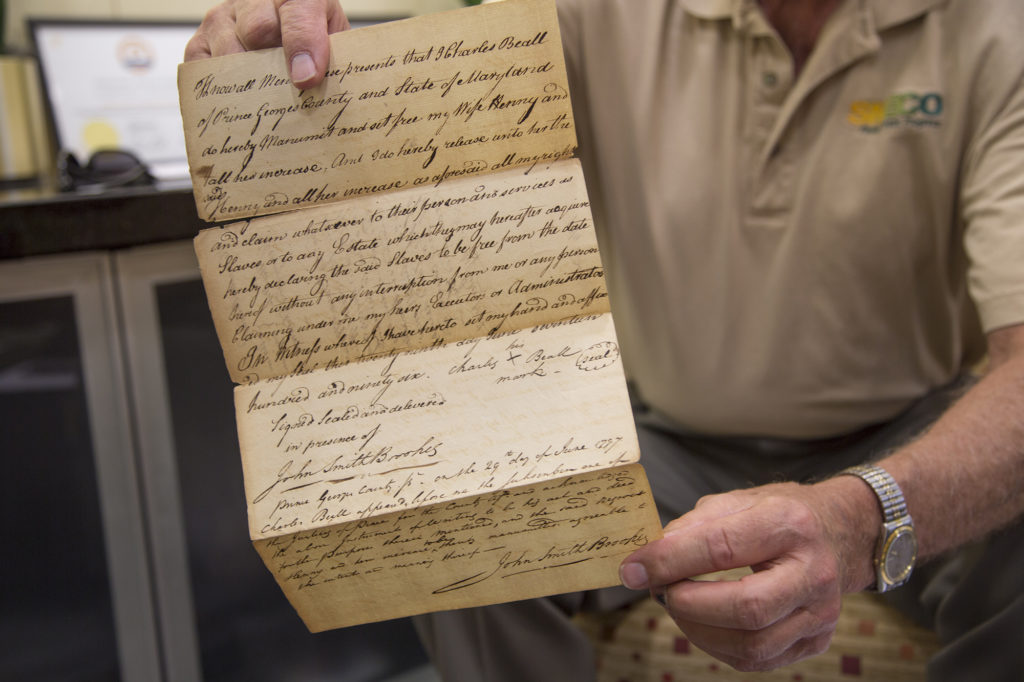

Written in elegant script, the dozens of manumission papers showed that some slaves were granted freedom outright or bought their way out. (Read the text of one of the slavery freedom letter’s from Dyer’s collection here.) In one, a father is purchasing his six-year-old daughter for $70. The papers are dated from 1781 to 1858.

“It’s an unbelievable collection,” said Laurie Verge, director of the Surratt House Museum in Clinton, Maryland, where 30 of the papers are on indefinite loan from Dyer, a director at Hughesville-based Southern Maryland Electric Cooperative.

“Primary source documents related to the institution of slavery are rare, and here are 30-plus such papers that tie particular slaves to particular owners and have been safely spared for over 150 years,” said Verge.

When the museum displayed a few of the papers that Dyer discovered, national attention followed. After a feature appeared in the Feb. 20, 2017, issue of The Washington Post, newspapers in Florida, Chicago, Arizona, California and even Yakima, Washington, picked up the story.

“I really didn’t think the papers would draw the interest that they have, particularly nationwide. They had been in a safe in our store and post office in Accokeek since the 1850s and, most recently, at my house,” said Dyer.

The safe’s contents are fascinating to researchers tracing their roots or wanting to “link white history with black history,” said Verge, who noted a surge in visitors after the Post story ran.

“The fact that we have already identified three plantation owners with freedom papers issued to the enslaved confirms this,” said Verge.

The papers also shed light on the complexities of manumission, the act of freeing a slave. In October 1838, Elizabeth Snowden, a wealthy widow in Prince George’s County, set two parents free, but their children were set free over a period of 20 years.

According to a museum librarian in the Post article, manumission laws discouraged owners from freeing slaves who couldn’t support themselves. “The aim was not to be benevolent, but to protect communities from the burden of caring for them,” the report said.

Dyer and Verge have two theories on who owned the documents and how they wound up on his property.

“My great-grandfather was the sheriff of Prince George’s County,” said Dyer, 74. “Some people might have filed the papers with him because he was a public official.”

“Another theory is that the safe was a place for people to keep old deeds and bills of sale. During the slave days, [freed people] kept their papers with them to prove their freedom” and kept the originals in the safe.

Dyer hopes to meet with an appraiser soon for estimates on the documents’ worth. In the meantime, he is digging through more documents, including one in which a Mr. Beall freed his wife in 1796.

Unraveling the mystery behind the papers has become “sort of like a hobby,” said Dyer. “You get going, and then you hit a roadblock. And then you start again.”

Victoria A. Rocha is a staff writer for NRECA.