The sporting boats and work trucks aren’t on the move for business or pleasure. They’re helping determined volunteers in the Cajun Navy save lives as widespread flooding from a deadly tropical weather system continues in Texas and Louisiana.

“We arrived in the Corpus Christi area during the hurricane, Aug. 25,” said John Billiot, of Scott, Louisiana, a member of Southwest Louisiana Electric Membership Corp. Billiot doesn’t command. He sort of “coordinates” activities for at least some of the volunteers rallied under a virtual banner of the Cajun Navy.

Plunging In

“Right now, I am sitting on a bridge near Beaumont, trying to deploy crews into Port Arthur and Vidor, Texas. Things are getting rough on the Sabine River,” Billiot said Aug. 30.

Dam releases on August 30 at the Toledo Bend Reservoir, coupled with continued rainfall along the Texas-Louisiana border, were sending high water down the lower Sabine, causing a record flood crest of more than 33 feet at Deweyville, Texas, and threatening communities downstream. “The water’s been 10 to 12 feet high in some places,” Billiot said.

“I’ve just removed my crews from Orange [Texas], and I got about 165 boats out here with me,” said Billiot. “About 45 of those are Lafayette buddies of mine, and the rest just kind of joined in.”

Pulling rescues day and night across the disaster zone, Billiot squeezes in a few hours sleep when he can. Then he works the phones, locating fuel and food for the mobile flotilla, reaching out for social media assistance from volunteers and finding likely hotspots before they become unreachable by pickup.

“People will call us and meet us at locations to buy gas; they’ll give us water, and offer what they can to help,” said Billiot. “We have airboats, we have [small outboard] bug boats, we have [flat bottom] gator tails, we have [large-tired, elevated suspension] skytop and highboy pickups, and we’ve got trailers.”

The gear is familiar to most hunters and anglers. But in countless subdivisions, mobile home parks, and sprawling communities of garden apartments, these boats in recent days have been a matter of life and death. That was particularly true in the days when winds and volatile storm bands kept helicopters grounded. As water levels rose beyond the depth reachable even by 4-wheel drive vehicles in the fleets of most local responders, these small boats were critical.

“We’re using what we’ve got to help people who are losing everything,” said Trent Buxton, a director at Beauregard Electric Cooperative, headquartered in Deridder, Louisiana.

Buxton arrived in the Houston area with his trailered boat, pickup truck and supplies, four days into the torrential downpour that began hours before Hurricane Harvey made landfall at Rockport. Members of his Deridder-based group, Rescue Rangers, quickly joined the hastily organized rescue flotilla of volunteers, from many groups, collectively branded The Cajun Navy.

“We worked one day in Harris County and the Houston area. Since then, we’ve been working in Port Arthur, Vidor and Orange,” said Buxton.

Throughout the tragedy, determined volunteers have made a significant difference, streaming into flooded areas with equipment, supplies and steadfast determination, and heading into floodwaters to save total strangers as if they were family.

Here to Help

“We’ve tried to get people to evacuate before the water started rising,” said Keith Blanchard, a SLEMCO meter technician who began supporting Cajun Navy rescue efforts near Moss Bluff, Texas, on Aug. 29. “Once people lost electricity, they started calling for help.”

As water levels rose, boats moved back and forth, heading in with blankets and empty plastic trash bags and then returning with people, with a few essential belongings and small pets, to areas where water was inches or just a couple of feet deep.

“We picked up a man in Pasadena about 3 a.m. Sunday and got him out so he could have kidney dialysis,” said Caleb Stark of Baton Rouge. “We helped pull people out of an area near Lake Houston where many two-story homes had five and six feet of water inside, and it was still rising.”

Those efforts were repeated again and again as an unknown number of volunteers worked side by side with, or independently from, first responders, pulling people out of a flood zone that stretched along hundreds of miles of coastline and inland more than 70 miles.

“We’ve been pulling people out, eight and 10 at a time, sometimes heading in with enough boats to bring out 12 to 15 families,” said Stark. “It’s been women and children first and the old people, then we’ll go back in and get the men.”

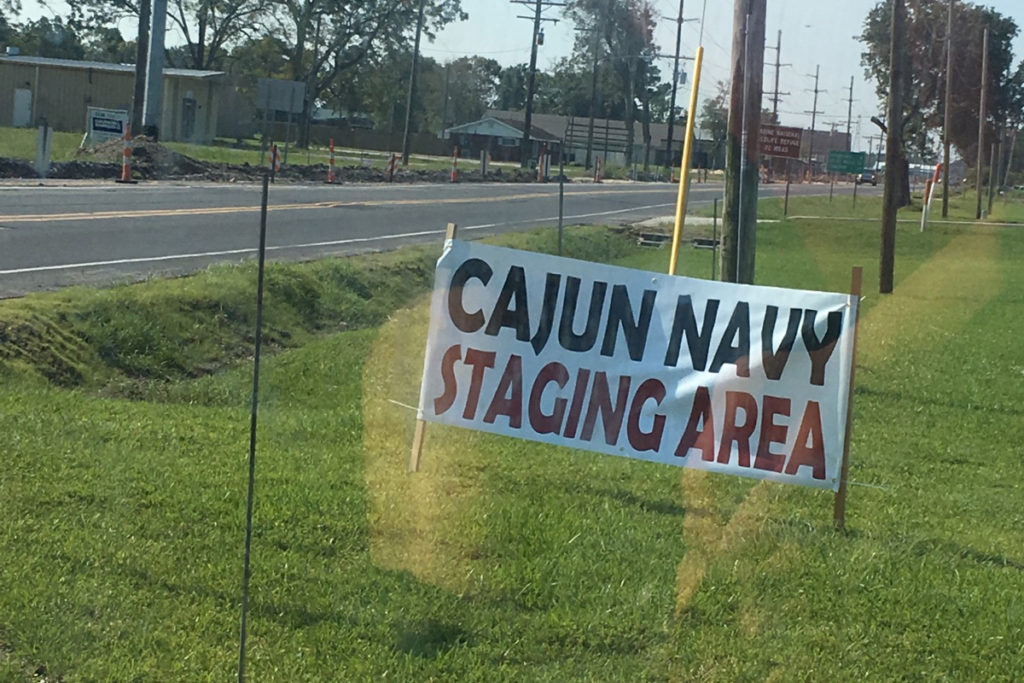

The boats have been used to transport flood victims from the murky waters, often to the edge of staging areas, like freeway overpasses, where they’re turned over to waiting Texas National Guardsmen or other first responders for transport to emergency shelters.

In many areas, the volunteers have quickly latched on to locals familiar with their neighborhoods, including some who’ve shown up on the edge of dry land on jet skis or sitting in single seat kayaks.

“They’ve been very important. They know where there are transformer boxes and other hazards, and where the ditches are, giving us a little more depth to operate,” said Stark.

Motivations–Why Ask Why?

While many people would do anything possible to save friends and family, most of the volunteers are heading deep into neighborhoods and communities they’ve never visited and where they know absolutely no one.

“Why wouldn’t I do it?” asked Billiot rhetorically. “Why would I just stand by and let people die or suffer because of Mother Nature?”

“They came to help us when we had flooding in Crowley, so we’re returning the favor,” said Mike Durand, of St. Martinsville, Louisiana, another SLEMCO member.

Friends organized under the name “Krew: We-Got-This,” trailered their boats into the Houston area on Aug. 27 before heavy downpours rendered portions of Interstate 10 impassable.

“We found a spot where we were needed and started helping out,” said Durand.

Members of the group learned water rescue on the fly when heavy rains dumped more than 20 inches of rain over the Southwest Louisiana in three days in mid-August 2016. They work currents, navigate through rain swollen drainage ditches and steer through water deep enough to handle flat-bottom or shallow draft boats, loaded down with flood victims.

“We started in New Caney, Texas, for three days and nights, then Wednesday we moved on to Beaumont,” said Durand, who is also a volunteer firefighter. “I’m prepared to work through the Labor Day weekend, wherever, I’m needed.”

As flooding subsides in one area, instead of heading home, many volunteers pack up, trailer their boats and immediately start looking for another location where rising waters threaten to displace more families.

“I was raised to believe that if you can help anyone, anywhere, you just do it,” said Benji Terro, of Lafayette, Louisiana, a Cajun Navy volunteer, and a member of Southwest Louisiana EMC. “We’re had flooding like this a lot in Louisiana, so these folks are in need. When you know what it’s like, you just try to help.”

Getting It Done

As roads from east or west have gone under, fresh volunteers with their boats and trailer rigs have continued to stream into flood affected area from north Texas and northwest Louisiana.

“Officials in Texas have understood we’re here to help, so they’ve given us clearance to pass through standing water in some areas where they public can’t go,” said Billiot. “We’ve been allowed to run with our emergency flashers on and get to where we are needed.”

Much of the success has been driven by social media. That includes urgent requests for rescue by frantic Facebook users; and constant chatter for hot meals, served up in a parking lot or at the edge of an impassable flooded road, or dry nearby churches.

“A business owner brought us out a pot of jambalaya. He did a live feed on his Facebook, and within 20 or 30 minutes, people were showing up with air mattresses for us to sleep on, water, and other supplies just for us. The church was empty and within 24 hours, you couldn’t fit any more stuff in there.”

Grateful People

“We don’t get negative comments. People are really glad to see us when we show up,” said Durand, of St. Martinsville, Louisiana. “Some of them have been standing in cold, muddy water for hours, trying to keep their kids and small pets dry. They’re really happy when we get them out.”

Survivors will remember this storm for what they’ve lost, but veteran volunteers, including some who’ve been in involved in water rescues for more than a decade, will recall the daunting scale of the disaster.

More than 24 trillion gallons of rain fell over south Texas and southwest Louisiana in four days, and urban flooding closed 300 major roadways, putting 1,300 square miles of development under at least one foot of water in Harris County, Texas, alone.

“Seeing all these people helping is a beautiful thing,” said Terro. “We’re all volunteers and we don’t expect anything out of it. We’re just doing what we were taught to do growing up in southwest Louisiana. That’s just who we are.”

Derrill Holly is a staff writer at NRECA.