Editor’s note: This is the fifth installment in our series of stories looking back at Hurricane Helene’s impact on electric cooperatives. Read the first four stories here.

If you fall behind on disaster communications, you’ll never catch up.

Which is why Daniele Ligons of Aiken Electric Cooperative was posting social media messages in the hours after Hurricane Helene from the front seat of her 2019 Honda Civic, its engine running so she could keep her smartphone charged.

“It was a crazy day. My phone was dying just as fast as I could charge it,” said Ligons, the co-op’s marketing and strategic services manager, who handled the blackout workflow with Jamacia McCray, her marketing and communicators coordinator, also confined to car battery power.

“I was talking to her, responding to members, figuring out what we should do with our posts and figuring out how to make the media aware of what we were doing. We were both glued to our phones the entire day.”

Hurricane Helene put 1.44 million electric cooperative members in the dark last September, and communicating with every one of them was Job No. 1. All co-ops are different and all storms are different, so no one-size-fits-all strategy kept members and the media informed. But the scramble was worth it because catastrophe can represent a unique opportunity for connection.

“We had 65,000 of our members with eyes all on us,” said Jim Donahoo, vice president of marketing and business development at Laurens Electric Cooperative in Laurens, South Carolina. “We had 100% of the media. We had all the public officials and the public in general with all eyes on us. We had that opportunity to shine, to deliver, to build value and demonstrate in a great way the value of being a member of Laurens Electric Co-op.”

It’s a given that members want information about storm prep and relief. But the numbers staggered Blue Ridge Energy in Lenoir, North Carolina. One of the hardest-hit co-ops, Blue Ridge had 70,000 members out of power—92% of its system—with many roads not just inaccessible, but gone.

We had 65,000 of our members with eyes all on us. We had 100% of the media. We had all the public officials and the public in general with all eyes on us.

Jim Donahoo, Laurens Electric Cooperative

The day after Helene devastated areas from Florida to Kentucky, then-Blue Ridge CEO Doug Johnson spoke for 90 seconds on a simple video to members. To date, the post has 558,000 views, 9,000 likes and nearly 850 comments—viral by any standard.

“I remember him joking at the time, ‘With the internet being down and the power being down will anybody even see it?’ And I said, ‘Oh, it will get out there,” said Renee Walker, the co-op’s director of public relations. “Getting that empathy out there early on and communicating what we were doing to restore power was very important.”

The deluge of responses came from outside the normal channel of Blue Ridge members, since many of them lacked cell or internet access. In this case, Walker found it was also people searching for information about the status of friends and relatives in the co-op’s territory.

“There was very little communication, very little infrastructure left in this area,” Walker said. “So we even had folks reaching out from the West Coast and different parts of the United States saying, ‘Hey, thank you. My son lives in that area. I haven’t heard anything from him. Your posts are the only thing I have from that area that resembles a media outlet.’”

Setting expectations

Most members interact with their co-ops on two occasions—when they get their bills and when the lights go out. Donahoo wanted interaction around the clock with Helene.

“Anything that we can do outside the scope of those two things by creating a positive experience and engagement is a great way for us to build good will with our members,” he said. “We wanted to be transparent, but keep them informed on an ongoing, hourly basis.”

That meant images of lineworkers doing their thing multiple times a day, sometimes posting on social media channels until midnight. “The theme of what we said set the expectations with our members and then we showed how we worked hard to overdeliver,” Donahoo said.

Laurens Electric timed regular media updates in the morning for noontime broadcasts, in the afternoon for the evening news and late night for 11 p.m. newscasts, always showing line crews hard at work.

At Aiken Electric, expectations came in the form of sticky notes on McCray’s office wall that set messaging for the day—updates during morning, afternoon and night hours.

“We wanted to reassure them each morning, ‘OK, we’re powered up, ready to go; this is the plan,’” Ligons said. “The afternoon post was more of damage or a testimonial from a member who was living with foxes and squirrels because a tree fell on the house. Then, in the evening, we put out what we had accomplished.”

The results were dramatic. With 67 posts, Aiken Electric’s Facebook page registered 2.18 million impressions during the two weeks of repairs and a 111% increase in followers. The co-op also introduced a bit of humor and gamesmanship in response to weary members who fretted about attentive service.

“People kept saying, ‘We don’t see your trucks.’ Of course, they were there; they might have been behind a tree. So we did a post on ‘Can you find the line truck?’” Ligons said. “That helped them to understand they are working; it just may not look like you expected. Our members responded well.”

Walker and Jacob Puckett, digital communications manager at Blue Ridge, managed the bombardment of communications requests, including Fox News, by focusing on one to three main points each day.

For example, some parts of Blue Ridge’s territory suffered medium levels of wind damage while others were hit with cataclysmic flooding. “There were completely different scopes of damage across our service area and we needed people to understand that,” Walker said. “I think the videos and photos helped a lot in showing what we were up against. Trying to respond to every message is impossible when you’re getting comments and direct messages coming in by the thousands, so picking up on trends of concerns and addressing those in our posts helped.”

There were completely different scopes of damage across our service area and we needed people to understand that.

Renee Walker, Blue Ridge Energy

Canoochee EMC in Reidsville, Georgia, also stuck to a regular system of reports in the morning and in the evening. Along the way, Communications Specialist Joe Sikes learned an important lesson—setting expectations via high-speed internet is not always the way to go.

“We made the decision that the CEO’s update was going to come in the evening after everything happened,” he said. “But when communication is down, you don’t want to do a video without words and some kind of written report. For some people, their internet, if they had any, was not fast enough to actually pull up a video. Everything we do is videos now, but Helene showed us sometimes you need to take a step back.”

CEO on camera

Van O’Cain has seen several storms as director of public and member relations at the Electric Cooperatives of South Carolina, but heading to stricken Little River Electric Cooperative in Abbeville was another experience altogether.

“I had never seen anything like that before. It was the oddest feeling to be driving and not having cell service, so the GPS was not working. The power was out everywhere and you’d go into town and none of the lights are working. So you’re having to go slow and make sure that you don’t wreck. The only sound you could hear would be generators.”

At about 15,000 meters, Little River does not have a full-fledged communications office, so O’Cain traveled several times to put interim General Manager Chad Stone on camera. Not slick, but genuine, just a couple of unscripted minutes outdoors explaining the situation to members.

“We felt it was important for Chad to be able to let his members know what was going on. His people were doing what they could to get the lights on as fast as they could. He needs to be out in the field doing his thing. So that’s how we did it with Chad,” O’Cain said.

A week after the storm, Aiken Electric CEO Gary Stooksbury stood amid downed limbs and lines, half a dozen broken poles on either side of him, to show firsthand why 15,000 meters were still out. “We are literally rebuilding the power system in parts of Edgefield County,” he said.

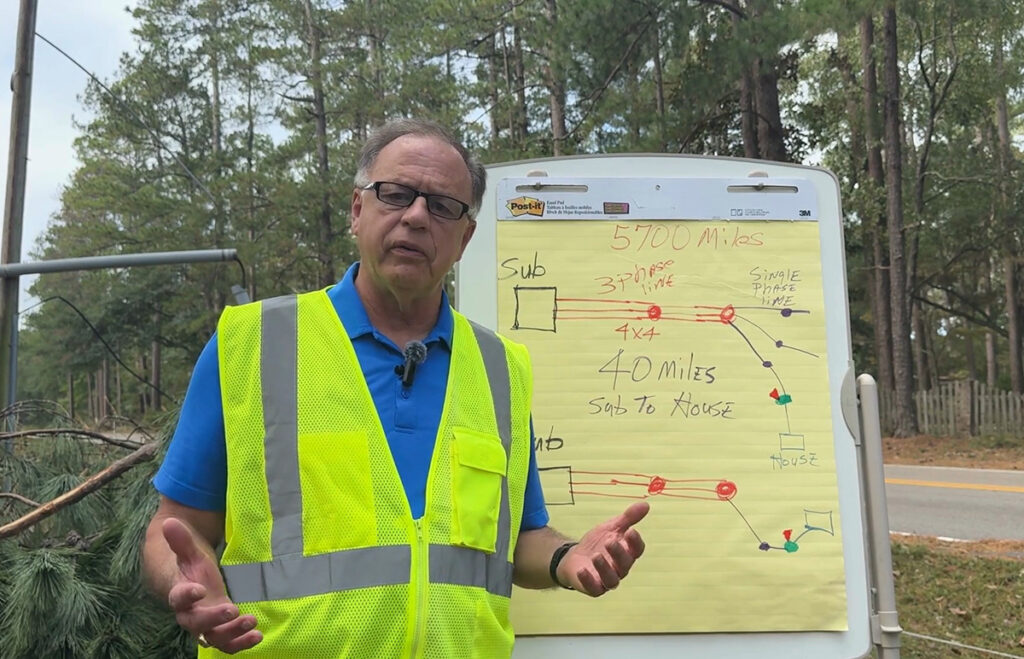

In another video, Stooksbury, in the field in a work vest, broke down the power restoration process by hand on a sheet of paper and answered typical questions, such as why one house on a road has power but an adjoining one is still in the dark.

Ligons said static charts and graphics have a place on social media, but a CEO drawing by hand in front of members carries a much bigger wallop. “It humanized things, which was part of our overall strategy. We’re local, we understand and we care, but it is not going to be easy,” Ligons said.

High winds and flooding battered Mountain Electric Cooperative in Mountain City, Tennessee, as hard as any co-op. Fourteen days in, General Manager Rodney Metcalf used a simple smartphone video to identify areas that needed work and explain how Helene wiped out even underground systems.

“We are coming. Just give us a little bit more time,” he said. One social media respondent was so impressed that he wrote, “This is what leadership looks like. So many companies could learn a lot from you and MEC.”

To Alisia Hounshell, director of communications and statewide services at the Florida Electric Cooperatives Association, the idea of getting the CEO on camera should be in every communicator’s playbook.

“When a CEO is behind a desk, he’s in an air-conditioned room that has power and he’s talking to an audience that is out of power. Here in Florida, we’re melting or we’re mildewing all at the same time. You want to see the CEO in the field, where they look like they’re working, so the viewer thinks, ‘He’s got his boots on the ground. That guy knows what he’s talking about.’”

Mutual communications aid

Jerry Edge has worked for 31 years at Little Ocmulgee EMC in Alamo, Georgia, and trees falling on his house were not about to stop him. Edge continued his work at the co-op, which maintains a small Facebook presence. Sumter EMC in Americus helped Little Ocmulgee with social media during Helene and that’s how Edge’s story flew across the internet.

“Nobody at our place or Jerry thought anything about the social media side,” said Lewis Sheffield, general manager at Little Ocmulgee. “His quote was, ‘That’s what I do. That’s my job.’ That’s an impressive attitude, but Sumter really opened our eyes to the need to put out there on Facebook for others to see.”

If the sixth cooperative principle is cooperation among cooperatives, its corollary might be cooperation among communicators. Knowing the 24/7 demand from members, the media and other parties, communicators at statewide associations and co-ops in less affected areas stepped up to help other co-ops.

In South Carolina, coastal co-ops such as Berkeley Electric Cooperative and Horry Electric Cooperative largely escaped Helene’s wrath but applied their big storm expertise to support Little River and Laurens, O’Cain noted.

“It was mutual aid among communicators,” he said. “They would help them with social media content or whatever they needed to help the communicators at the most affected co-ops get a little bit of a break. That was something I had not seen that before in our state, so it was beyond the statewide that co-ops were helping co-ops.”

Posts did not have to be tied directly to line work, either. A road safety message from North Carolina’s Electric Cooperatives did overwhelming numbers—nearly 6,000 likes and 2,500 shares on Facebook.

“Co-op lineworkers put their lives on the line every day. If we can support them and the critical work they do by amplifying a strong safety message, that’s a priority for us,” said Townley Venters, director of communications at North Carolina’s Electric Cooperatives.

Hounshell is a big advocate of enlisting another cooperative as a backup when a storm is on the horizon. While at Talquin Electric Cooperative in Quincy, Florida, she turned over the social media account to another co-op communicator in the state for a couple of days once Hurricane Michael hit in 2018.

“Again, it’s setting those expectations. We knew we might lose communications, but we could not afford to go dark,” she said. “There’s always room for improvement and you can’t be so stuck one way and doing one thing that you won’t budge and do something else. You have to pivot in a heartbeat.”

Coming next week

Around 1,500 lineworkers from 175 electric cooperatives were part of the massive mutual aid effort to restore power after Helene. The next installment of our series puts the spotlight on crew members who traveled from states far outside the Southeast with conviction bred in their bones to help others.

Contributing writer Steven Johnson is a former managing editor at NRECA, where he started in 2005, and former editor of Cooperative Living and vice president at the Virginia, Maryland & Delaware Association of Electric Cooperatives.

Banner Image Courtesy Little Ocmulgee EMC