Editor’s note: This is the fourth installment in our series of stories looking back at Hurricane Helene’s impact on electric cooperatives. Read the first three stories here.

In 2019, in the shadow of Hurricane Dorian, Danny Shelley, the new CEO at Horry Electric Cooperative in coastal South Carolina, sat at dinner with mutual aid crews including Chad Stone, a line foreman at Little River Electric Cooperative.

“This hurricane is coming and I haven’t been in this job six months,” Stone recalled a concerned Shelley saying. “I just want to let you know I appreciate you.”

The words stuck with Stone. In September 2024, he was the new interim general manager at Little River Electric Cooperative when an unthinkable hurricane shook his inland co-op to the core. Teams from Horry Electric were there the next day and would eventually outnumber the entire Little River staff.

The situation was reversed. You’ll excuse the catch in the Stone’s voice.

“This is what they kept saying: ‘We are not leaving till every light is on.’ And the ones that went home didn’t want to. They said, ‘We’re coming back, Chad, we’re coming back. We’re not gonna leave y’all until every light is on.’”

A war movie

Off a beaten path in Abbeville, about 90 miles west of Columbia, Little River has a little more than 15,000 meters. It is a blueprint for the tightly knit, small-town co-op, where everybody knows each other, wears multiple hats and takes pride in treating people with respect. Stone went to school with Tricia Smith, member service and communications director; he and Mike Hall, vice president of engineering services, have each put in more than 30 years at the co-op, which has 32 full-time staffers.

“Most of us that work here knew each other at some point long before we came here. We already had friendships before we came,” Smith said. “When we come to work here, you are already part of the family because you’ve known that person forever.”

When we come to work here, you are already part of the family because you’ve known that person forever.

Tricia Smith, Little River Electric Cooperative

As Helene approached, the family needed outside help. Anticipating the damage high winds could do to the oak and pine forests across Little River’s four-county territory, Stone asked the South Carolina statewide association to locate extra crews, figuring that his team could take care of about half of any situation.

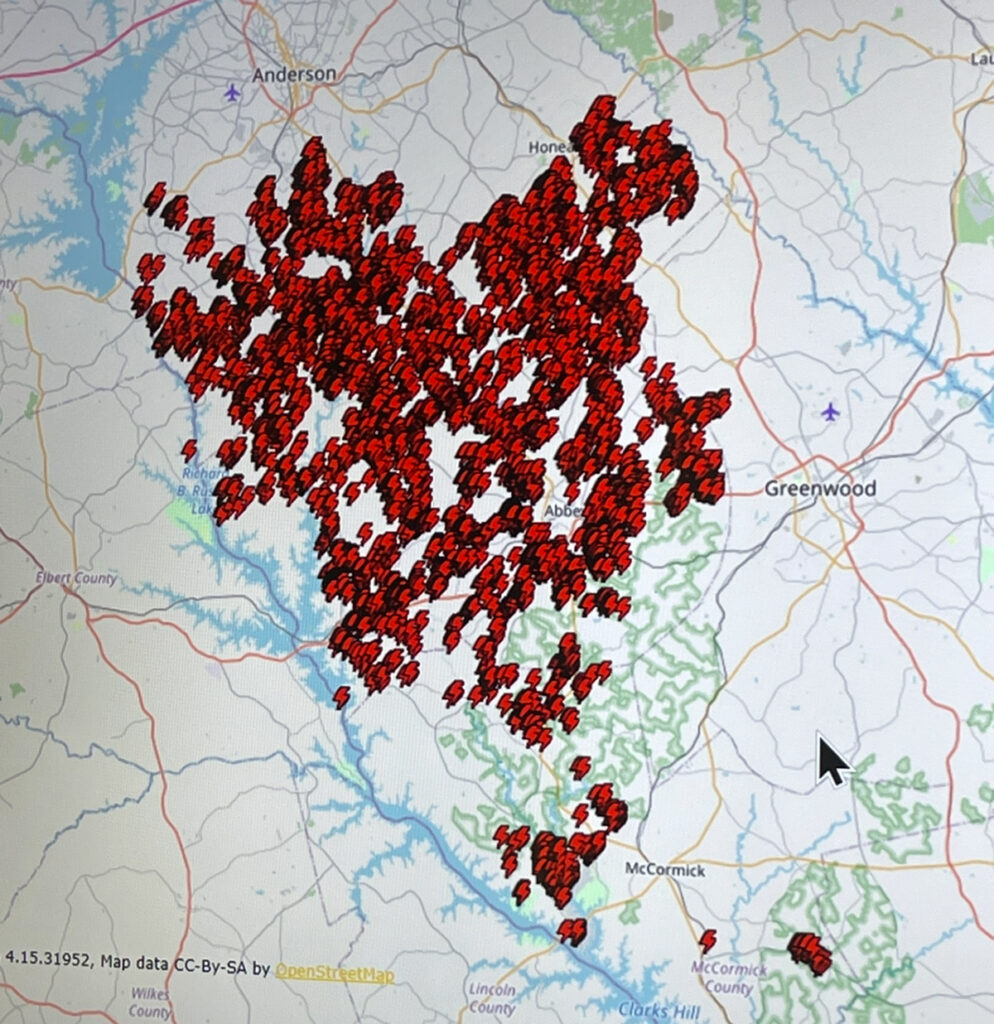

The red dots showed otherwise. They flashed on the outage map screen in Hall’s office, one on top of another, outage after outage, on the morning of Sept. 27, 2024, until just about all of the co-op’s members were in the dark.

“It reminded me of those war movies when people are in the Defense Department and looking at the map of all the places that are going to be bombed. And this was kind of a bombing in a way. That was what we felt like,” Stone said.

Anecdotal evidence backed it up. Stone had called all lineworkers into the office, but a three-foot-wide pine tree blocked one crew member’s return after he had responded to a car trapped under a power line.

“We started going out to try to get to him and we couldn’t. No road was passable that quickly. It took us probably 30 minutes to finally get around trees and go this road and that road to get to him,” Stone recalled.

Once located, Stone and the lineworker found themselves on opposite sides of the immovable tree. Stone had planned to pick up an order at Cold Springs Cafe. With his path stymied, the lineworker went in his place, only to find the store pushing water out the front door.

“That is when I really realized that it was going to be 15 days or so before we got things under control,” Stone said.

From here to there

The morning after Helene hit, Horry Electric and Little River were going in opposite directions at the same time with distressingly poor prognoses.

Conway-based Horry Electric quickly brushed off Helene’s impact, restoring power to about 9,000 members within a few hours. On Sept. 28, four six-man line crews and engineering personnel set out west from Horry Electric to Abbeville, a four-hour-plus ride in normal conditions. As they got to the city of Newberry, it was time to refuel the trucks. But that was not going to happen.

“Everything was dark, no power, not a store or station was available, so we said we’ll just go as far as we can,” said lineworker Chad Tyler. They drove another 50 miles. Fallen pine trees everywhere. A bucket truck could barely squeeze by on some roads.

“The entire system, north to south, was destroyed. So overall their damage was way more than what we’ve ever experienced here since I’ve been here,” said supervisor Franklin Williams. “It was two days before we could really see all the damage.”

As line crews tried to make sense of things, Little River confronted the need to feed and care for a rush of visitors that eventually would number about 180 lineworkers. A preorder of sandwiches and biscuits proved to be inadequate, and a small team of employees from the office headed east in four SUVs around 9 a.m. to buy groceries in nearby Greenwood even as Horry Electric crews headed toward them.

Everything was dark, no power, not a store or station was available, so we said we’ll just go as far as we can.

Chad Tyler, Horry Electric Cooperative

It was a disaster. There was nothing in Greenwood. Every store was closed, every road was blocked. Turn around, find another road, find another blockage. On their own, they headed to Columbia, about two hours away. At headquarters, Smith became concerned. “We had no communication. I couldn’t call them. I had no idea where they were. And I was like, ‘Why is it taking so long?’” It was nightfall when they finally pulled into the Little River lot.

“Columbia’s not a hard ride, but they said it was so bad they could not get there. It took three or three-and-a-half hours,” Smith said. “And they were exhausted and tired and emotional because it had taken them about 10 hours to go get some groceries. They brought all that food back in four SUVs and we were like, ‘Gosh, this will last for days.’ Our food was gone in two days.”

With the community’s help, the co-op started to find a groove. Retirees came in to help. A local restaurant with a food truck made some dinners. Headquarters became Grand Central Station South as donations of food and ice turned the office into a food pantry. A member donated a refrigerator. “We had so much food we didn’t know where to put it,” Smith said. Staffers worked from 4 a.m. to 11 p.m. so they’d be the first to arrive and the last to leave; Smith slept on an air mattress for nine nights.

A local doctor volunteered his house; that provided several comfortable beds for weary lineworkers. The fire station opened its doors, while other workers stayed at the house of Hall’s mother, a prominent educator who died three months before Helene. “We were buying cots and blow-up mattresses and blankets and pillows, putting them wherever we could,” Stone said. “I’m thankful that the crews didn’t know what was going on behind the scenes. All they knew was they had a place to go.”

Reinforcements arrive

Stone has a display of framed, color 8x10s of his heroes on one wall of his office. They’re not of sports stars or celebrities, though. They’re photographs of the dozens of line crews that came from points near and far to help Little River in its darkest hour.

Like Dave Monson, materials coordinator at Nishnabotna Valley REC in Harlan, Iowa, who traveled 1,100 miles as a part of a four-man team, waited out a three-hour traffic delay in Atlanta and labored 16 hours a day for 10 days in working his first hurricane.

“Being from Iowa, you don’t realize the amount of trees,” Monson said. “A lot of their structures just jump at angles through the trees. Almost every pole they had was at angles. The biggest thing I noticed right away, as we were driving into the hurricane damage, was how many trees were uprooted versus just broken off.”

At night, Monson and his partners ended up in a historic hotel in Abbeville. “Come to find out, after we were there a couple of days, it was haunted. We didn’t see anything but it was just kind of an interesting little story,” he said.

The biggest thing I noticed right away, as we were driving into the hurricane damage, was how many trees were uprooted versus just broken off.

Dave Monson, Nishnabotna Valley REC

Out-of-state crews arriving a week after the storm found the challenges just as daunting as the first responders from Horry Electric. About 400 poles were down. A Dominion transmission outage presented a major complication in a portion of McCormick County, south of Abbeville. Little River couldn’t think about restoring power until that was fixed, which took nearly a week.

“If it wasn’t broken poles, it was wire on the ground or broken crossarms or some of that nature—everything from a three-phase pole to a service pole,” said crew foreman Jason McKinney, one of eight mutual aid lineworkers from Mecklenburg Electric Cooperative in Chase City, Virginia. “It was wild, all those roads with trees still across them.”

Little River was not sufficiently staffed to dispatch bird dogs, the term given a coordinator who appraises and supervises an area of repair. Lineworkers from Horry Electric stepped in and filled the vital role of leading and directing crews in the field.

“The help from the outside, it was just awesome. Maybe we could have done it without them, but it would have taken a lot longer and been a lot more painful,” Hall said. “We want to safely get everybody’s lights on as soon as we can. We like to take care of ourselves. But sometimes you need help.”

The Little River staff also wanted to make a good first impression on its visiting lineworkers. “I always say if you want respect from them, you better give them respect,” Hall said. From his experience on the ground during Hurricane Katrina, Stone knew the value of keeping a stockpile of supplies at hand. “We had headache medicine, we had socks, we had belts, we had everything. It was like a buffet every day and they appreciated that.”

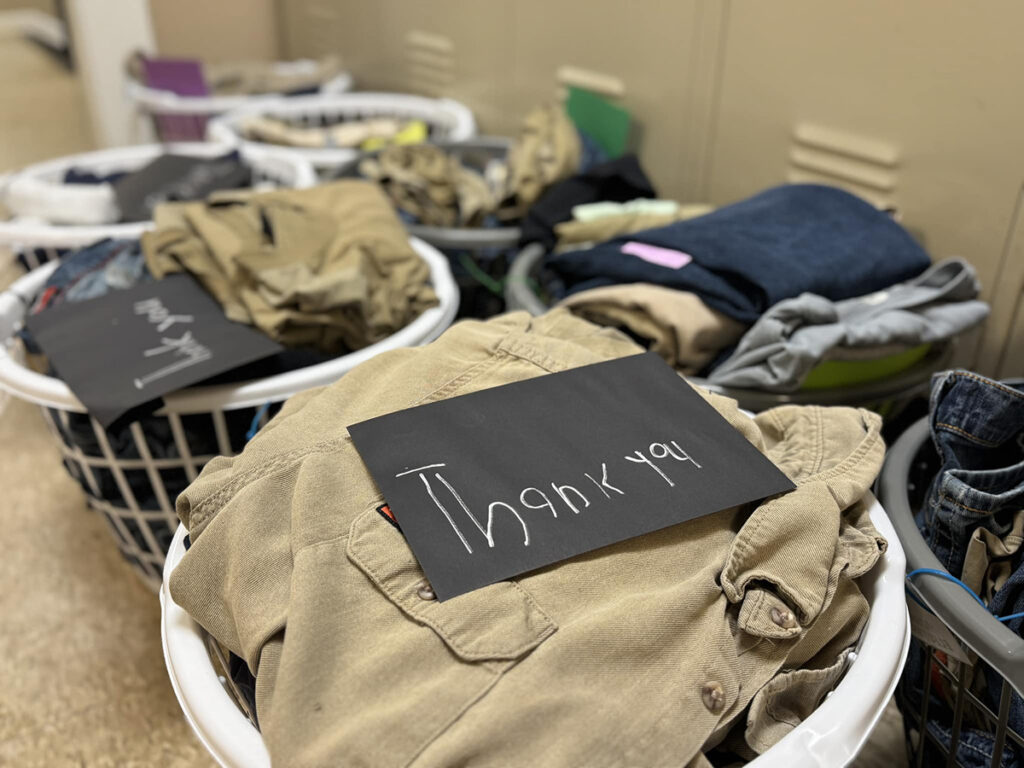

Staffers, volunteers and employee spouses tended to lineworkers’ laundry every night. When the laundry came back in the morning, each basket was topped by a handwritten card or note from a child via a school or a church.

“There were notes everywhere with your lunches and everything from kids, members … I mean it was pretty amazing,” Monson said. “Almost every morning they had a devotional prayer for us. They really made it made you try to feel as close to home as you could.”

And Little River came full circle from the night when Shelley sat down with Stone and other crews at the onset of Hurricane Dorian. “They weren’t just a face; they were somebody we actually sat down with every night at dinner,” Smith said. “We would go from table to table or just greet them. I think that helped. It was like they were the same people from a whole different state.”

Chicken bog

Horry Electric did not let up by any means; in fact, it forestalled some of its work at home so its lineworkers could help Little River and other co-ops. Shortly after the storm hit, Horry Electric announced extended waiting times for new service requests, generator installation and outdoor light repairs so employees could focus on Helene restoration.

“They were not hooking up new connections as quickly as usual because so many of them were here and at other co-ops,” Stone said. “That was something their membership lost, but it was to help another community. That just really stuck out to me.”

Horry Electric’s communications team helped with social media posts and images sent by its lineworkers, and one of its retirees cooked a massive chicken bog as a celebration for all the good work done by the line crews.

“It’s rice, chicken, sausage, onions, a bunch of different seasonings. They brought it in these cast iron pots, just loads of them. That must be a tradition down there. It was new to me, but I tell you what, it was good,” said McKinney of Mecklenburg Electric. In fact, two members of his team cooked a chicken bog of their own when they returned home.

Stone also took note of a budding relationship between Horry Electric and the pastor of a small church in a troubled part of Little River’s territory. “They brought a huge trailer of supplies and were taking it to that community, and they dropped off supplies for that church to distribute. They had a horse trailer; it was that full. Then when they left here, they went straight to North Carolina to drop off more things. So they didn’t just help us. They were helping as many people as they could.”

That, he said, represents the best of the cooperative community and helps to explain the ties that bind Little River and Horry Electric.

“When their crews were leaving, there was a strong sense of gratitude and mutual respect shared between us,” Stone said. “That relationship we made with that co-op is like no other one you ever will see.”

Coming next week

In the next installment of our series, learn how co-op communicators rose to the monumental challenge of keeping members, elected officials, regulators and the media informed with news that was honest, encouraging and realistic.

Contributing writer Steven Johnson is a former managing editor at NRECA, where he started in 2005, and former editor of Cooperative Living and vice president at the Virginia, Maryland & Delaware Association of Electric Cooperatives.

Banner Image Courtesy Little River EC